According to a study by researchers at the University of Trento, radar data point to what looks like an enormous lava tube in the Nyx Mons region of Venus. The study, recently published in a multidisciplinary journal, Nature Communications, suggests the underground structure could stretch for dozens of kilometers and dwarf similar formations on Earth.

The evidence comes from a new analysis of decades-old spacecraft data.

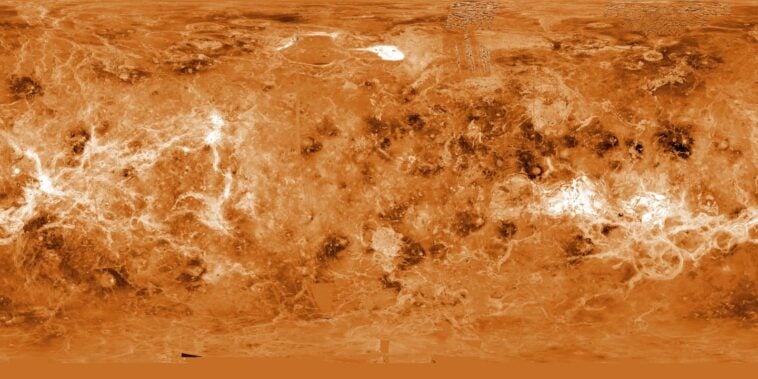

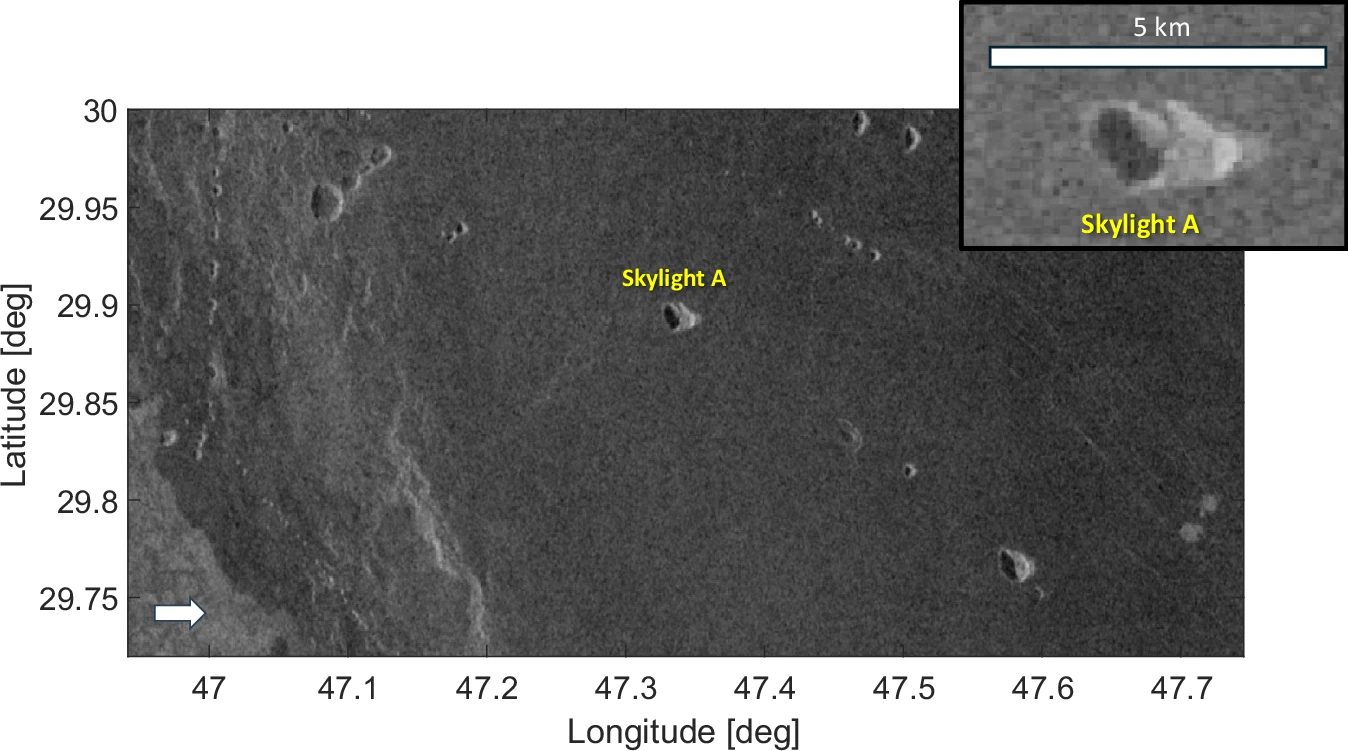

Between 1990 and 1992, NASA’s Magellan mission mapped Venus using synthetic aperture radar as the planet’s thick cloud cover blocks conventional cameras. The Trento team applied a recently developed radar imaging technique to those archival images, focusing on areas where the surface appears to have partially collapsed.

What they found was a skylight, essentially a pit that seems to open into a much larger cavity below. Based on radar signatures and terrain modeling, the researchers estimate the tunnel is about one kilometer wide, with a roof at least 150 meters thick and a void extending at least 375 meters deep.

“We have never had the opportunity to directly observe processes occurring beneath the surface of Earth’s twin planet,” said Lorenzo Bruzzone, lead author of the study and head of the University of Trento’s Remote Sensing Laboratory. “This discovery contributes to a deeper understanding of the processes that have shaped Venus’s evolution and opens new perspectives for the study of the planet,” he added.

The find is significant partly because of how these structures form — and how Venus’s extreme conditions might make them uniquely massive.

How volcanic tunnels take shape

Lava tubes form when molten rock flows away from a volcanic vent and the outer layer cools into a crust. The Lava then continues moving underneath, carving out a tunnel. On Earth, they can stretch for kilometers. Similar features have been spotted on the Moon and Mars.

But Venus, with its lower gravity and dense atmosphere, may allow even larger tubes to form. The team believes conditions on the planet could help molten lava develop a thick, insulating crust quickly, preserving large underground channels. The structure detected at Nyx Mons appears bigger than most lava tubes on Earth and larger than those predicted for Mars. Its scale matches other outsized volcanic features already mapped on Venus.

What comes next

So far, the confirmed portion is limited to the area near the skylight. But the surrounding terrain tells a larger story. The pit appears to be part of a collapse chain—a winding line of similar surface depressions that typically marks the path of a buried lava tube. Based on the pattern and spacing of these features, the underground conduit could extend for at least 45 kilometers.

To know for sure, scientists will need sharper tools. Two upcoming missions could provide them: the European Space Agency’s EnVision spacecraft and NASA’s Venus orbiter, VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy).

Both will carry advanced radar systems designed to map Venus in far greater detail. EnVision is also expected to include a Subsurface Radar Sounder (SRS) capable of probing hundreds of meters below the surface.

Bruzzone calls the finding a starting point rather than a conclusion. So, Venus is pretty much still one of the least understood rocky planets, despite often being described as Earth’s twin. Its surface is young in geological terms, reshaped repeatedly by volcanic activity.

This newly identified tunnel adds another layer to that story and a reminder that even beneath a planet long studied from orbit, there are still gaps in the map.

Sources: University of Trento, Nature Communications, SciTechDaily