File this under: things that sound like science fiction but are 100% real.

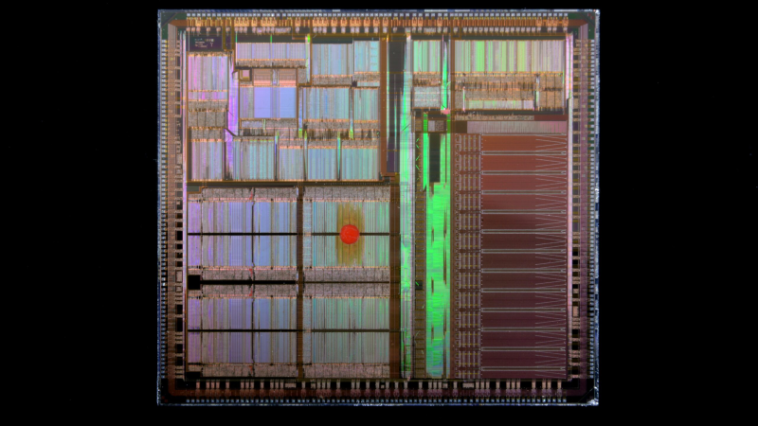

A researcher at the University of Colorado Denver has developed something that, on paper, sounds impossible—a chip the size of your thumb that can do what used to take massive, mile-long particle colliders to pull off.

What does that actually mean? Two things: this chip could one day help doctors destroy cancer cells with incredible precision, and it might help physicists answer the weirdest question in science—are we living in a multiverse?

Let’s break it down. Dr. Aakash Sahai, the guy behind the tech, figured out how to create ultra-intense electromagnetic fields using a silicon-based material. Until now, if scientists wanted to generate those fields, they needed enormous facilities like the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. Those take up miles of space and billions of dollars. This? It fits in the palm of your hand.

That alone is wild. But here’s where it gets even crazier.

In medicine, those extreme energy fields could eventually power gamma ray lasers—yes, real gamma ray lasers. If developed safely, they could be used to target cancer at the atomic level. Not whole cells. Not tissues. Literally at the nucleus of an atom. That means zapping cancer without touching the healthy stuff around it. No invasive surgery. No collateral damage. Just precise, microscopic edits to the body.

And then there’s the physics side. Sahai’s chip might actually let researchers test theories about the multiverse—like, the kind of questions you hear in documentaries narrated by Morgan Freeman. The tech opens up experiments we’ve never been able to run before because we didn’t have anything strong enough, small enough, or safe enough to do it.

Right now, it’s still early days. Sahai and his grad student, Kalyan Tirumalasetty, are heading back to Stanford’s SLAC accelerator lab this summer to keep refining the design. But the foundations are already solid—CU Denver has filed patents, and the chip has been featured on the cover of a top-tier quantum science journal.

Will this thing be curing cancer next year? Probably not. But in a decade? Maybe. In the meantime, it’s got scientists genuinely excited, not just because of what it can do—but because of what it might reveal.

Source: Science Daily