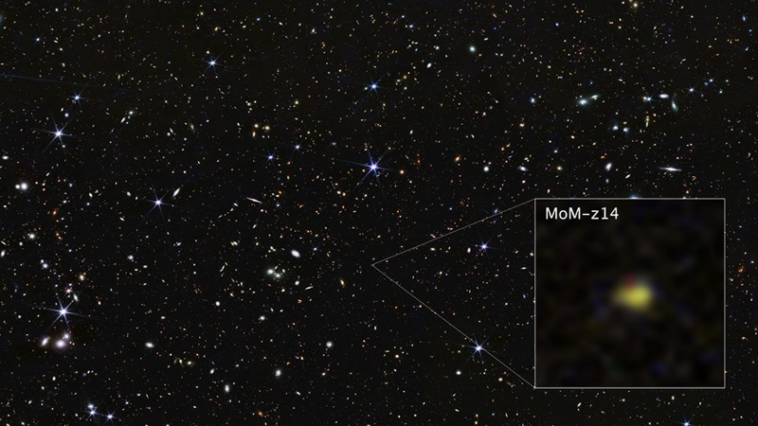

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has confirmed the existence of a bright galaxy that formed just 280 million years after the big bang, pushing observations deeper into the universe’s earliest period than ever before.

The galaxy, known as MoM-z14, was confirmed using Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph, which measured a redshift of 14.44. That means the light now reaching Earth has been traveling through expanding space for roughly 13.5 billion years.

Researchers say the discovery adds to a growing body of evidence that the early universe contained far more bright, massive galaxies than theories predicted before Webb launched.

“With Webb, we are able to see farther than humans ever have before, and it looks nothing like what we predicted,” said Rohan Naidu of MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, lead author of the study published in the Open Journal of Astrophysics.

Confirming MoM-z14 required more than imaging alone. Astronomers used spectroscopy to verify its distance and age, a step researchers say is essential when studying objects this far back in cosmic history.

“When you’re looking this early, estimates aren’t enough,” said Pascal Oesch of the University of Geneva, a co-principal investigator on the survey. “Spectroscopy tells us exactly what we’re seeing and when it existed.”

MoM-z14 is part of a larger pattern Webb has uncovered since beginning operations. The telescope has identified dozens of early galaxies that are significantly brighter than expected. According to the research team, the number of such galaxies is roughly 100 times higher than pre-Webb models predicted.

One unusual feature of MoM-z14 is its chemical makeup. The galaxy shows elevated levels of nitrogen, despite forming so soon after the universe began. Under conventional models, there would not have been enough time for multiple generations of stars to produce that amount of nitrogen.

Researchers suggest the conditions of the early universe may have allowed for extremely massive stars capable of generating heavier elements much faster than stars seen today.

The galaxy also appears to be clearing hydrogen gas in the space around it, offering new clues about the timing of cosmic reionization. This was the period when early stars and galaxies began breaking through the dense hydrogen fog that filled the young universe, allowing light to travel freely through space.

Mapping that transition was one of Webb’s primary science goals. Until now, astronomers lacked direct observations from this era.

Webb’s findings build on earlier discoveries made with the Hubble Space Telescope, including the galaxy GN-z11, which existed about 400 million years after the big bang. Webb later confirmed GN-z11’s distance and has since identified even earlier galaxies.

Astronomers expect the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to expand this work further by surveying much larger areas of the sky, potentially identifying thousands of similar early galaxies.

“To understand what’s happening in the early universe, we need both depth and numbers,” said Yijia Li, a graduate researcher involved in the study. “Webb gives us detail, and Roman will give us scale.”

The James Webb Space Telescope is operated by NASA in partnership with the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency.

Why this all matters

The confirmation of MoM-z14 isn’t just an exciting development for NASA – it’s a total reimagining of our cosmic roots. By literally peering into this ancient light, we are watching the universe “turn the lights on” for the very first time.

As the Webb telescope continues to peel back the layers of time in space—and the Roman telescope prepares to join the hunt—we are quickly realizing that the early universe wasn’t a dark, empty void the way we thought it was. In fact, it was a brilliant, busy nursery, and we are finally getting our first look at where it all began.

Source: NASA